From Gombe to Global Change: Jane Goodall’s Enduring Influence on Wildlife and Humanity

Jane Goodall stepped into a world of science that was, at the time, shaped almost entirely by men. Without formal scientific training, she faced criticism from some researchers who felt her methods were too personal or lacked objectivity.

But that personal touch was exactly what made her work revolutionary. She named chimpanzees and connected with them as individuals, each with their own personality and emotions, rather than just research subjects—opening a window into their lives that hadn’t been seen before. Her empathy didn’t weaken the science; it transformed primatology and our understanding of animal behaviour.

Goodall often reminded us that real change starts with the choices we make every day. Even the smallest actions, when multiplied, can create powerful ripple effects. As she said, “You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you. What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

Named a United Nations (UN) Messenger of Peace in 2002, the UN paid tribute to her legacy after her death, writing on X: “(She) worked tirelessly for our planet and all its inhabitants, leaving an extraordinary legacy for humanity and nature.”

Her sense of interconnectedness—and belief that even small actions matter—was born in the forest. There, through quiet observation and immersion in the wild, she listened. Not just to the chimpanzees, but to the insects, the trees, and the earth itself. She came back with a message: all life is sacred, and we are part of a vast and delicate web. Her work urged us to reconnect—with each other, with nature, and with the smallest creatures whose wellbeing is tied to our own.

As we say goodbye, it’s up to us to carry forward her message of hope and humanity. In a 2022 speech at Washington University in St. Louis, she reminded us, “We’ve just got this one beautiful planet—it’s our one home, and it’s what we have to save. I think the problem is there’s been a disconnect between the clever brain and the human heart, which is love and compassion. I truly believe that only when the head and heart work in harmony can we attain our true human potential.”1

Born Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall on April 3, 1934 in London, England, she was fascinated by animals from her earliest childhood.

When she was about a year old her father gave her a stuffed toy chimp called Jubilee, a gift that seemed to predict the lifelong connection to the primates that would shape her career. Family friends thought she’d be scared of the toy, but the opposite was true—Jane adored it, and kept it her entire life.2

Early on there were signs of the qualities that would be valuable for her research work. At four-and-a-half years old, she gave her mother a scare when she disappeared for five hours on a visit to a country farm. After a frantic search, Jane was found in the henhouse, patiently watching a chicken about to lay an egg.3

She often recalled that, instead of scolding her, her mother encouraged her curiosity—support that helped lay the foundation for her future career.

Alongside her curious spirit, as a young girl Jane also loved reading books about animals—including Tarzan of the Apes (featuring a character named Jane, the adventurous heroine), The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling, and the Dr Dolittle series, about a man who could talk to animals. She dreamed of travelling to Africa one day to work with animals and write about them.4 She never imagined becoming a scientist—back then, it was just wasn’t something girls did.

Much of her early childhood was spent in the English seaside town of Bournemouth, in a household of women—her mother, Vanne, a novelist; her grandmother; her younger sister, Judy; and two aunts. Her father, who drove for the Aston Martin racing team and served during and after the war as an army officer, was away much of the time. After her parents divorced in 1950, the house remained a place where thinking and learning were encouraged, and she was nurtured by support and encouragement from her mother and other family members.

Her mother’s words left a lasting impression: “Work hard, take advantage of opportunity, but above all, never give up. Surely you’ll find a way.” She would go on to share this message with young people around the world, inspiring them to follow their own dreams.

That same curiosity and determination would eventually lead her to a life-changing encounter. Unable to afford college after graduating, Goodall went to secretarial school in South Kensington and took jobs as a waitress and with a documentary film company.

In 1957, when a school friend invited her to visit their family’s farm in Kenya, she jumped at the chance, having saved up enough for the trip. Not long after arriving she met the renowned paleoanthropologist, Dr Louis Leakey, who was to become her mentor.

Leakey had been searching for the right person to study chimpanzees in the wild for some time. He believed that observing great apes in their natural habitat could offer clues about human evolution—and that someone without formal scientific training might bring fresh eyes and an open mind to the work. Seeing Goodall’s natural curiosity and intuitive connection to animals, he hired her first as his secretary and assistant, then arranged for her to study primate behaviour in London.5

After securing funding, he commissioned Goodall to begin a chimpanzee study in 1960 in the forests along Lake Tanganyika—land that would later become Gombe Stream National Park, now known simply as Gombe National Park.6

Goodall was 26 when she arrived on the lakeshore in July of that year. British colonial authorities didn’t allow her to stay in the forest alone, so her mother accompanied her for the first four months of the trip.7

Venturing into a narrow, forested strip along the eastern shore, Goodall began observing the Kasekela chimpanzee community in their natural habitat. At first she watched them from a distance with binoculars.8 She would often walk miles without seeing a chimpanzee, covering rugged terrain through thick vegetation.9

In time, an older male chimpanzee with white hairs on his chin—whom she named David Greybeard—came to trust her. At the time Goodall wasn’t aware that the scientific community used numbers rather than names to identify animals, believing that this helped them stay objective and emotionally detached.

The breakthrough moment in her relationship with David Greybeard came after she followed him through the forest and offered him a palm nut. He accepted it, then dropped the nut and gently squeezed her fingers—as chimpanzees do to reassure each other. As a high-ranking male in the Kasekela community, David Greybeard’s trust opened the door for other chimpanzees to let her into their world.

The behaviours Goodall documented changed the way we understand our closest animal relatives. She revealed that chimpanzees live complex social lives, forming deep social bonds and expressing emotions once thought to be uniquely human. These discoveries overturned long-held assumptions and reshaped our understanding of the boundary between humans and other animals.

Just as humans have distinct personalities, so too did the chimpanzees she came to know. David Greybeard, her favourite, was calm, trusting and determined. The alpha male, Goliath, was tempestuous; Frodo a bully; Flo, a nurturing and attentive mother.

She witnessed acts of kindness, like orphaned young being adopted by unrelated members of the group.

But she also saw a darker side. One young chimp grew depressed and died after losing his mother. Other behaviours challenged her early belief that chimpanzees were more peaceful than humans: males using aggression to assert dominance, and when the group split into two rival factions, she observed organised, sustained violence—and murder. Her work suggested that many aspects of human behaviour reflect those seen in apes. “I felt I was learning about fellow beings capable of joy and sorrow … fear and jealousy,” she said of the time.10

She first realized that chimpanzees were making and using tools when she saw David Greybeard stripping the leaves from a twig and using the slender stick to fish termites out of a mound. Until then, scientists believed tool-making was a uniquely human trait. When she shared her discovery with Leakey, he famously replied: “Now we must redefine ‘tool’, redefine ‘man’, or accept chimpanzees as humans.”11

Although most of their diet is made up of nuts, fruit, seeds, leaves, flowers, and insects, Goodall saw chimpanzees hunt and eat meat, using sophisticated cooperative strategies. Meat made up less than 3% of their diet, but until then, they were thought to be herbivores.

With support from Leakey, Goodall began her PhD studies at Cambridge University in 1962, returning often to Gombe for fieldwork. She was only the eighth person accepted at Cambridge for a doctorate without first earning an undergraduate degree. She completed her PhD in Ethology—the study of animal behaviour—in 1966, and continued working at Gombe for the next twenty years.

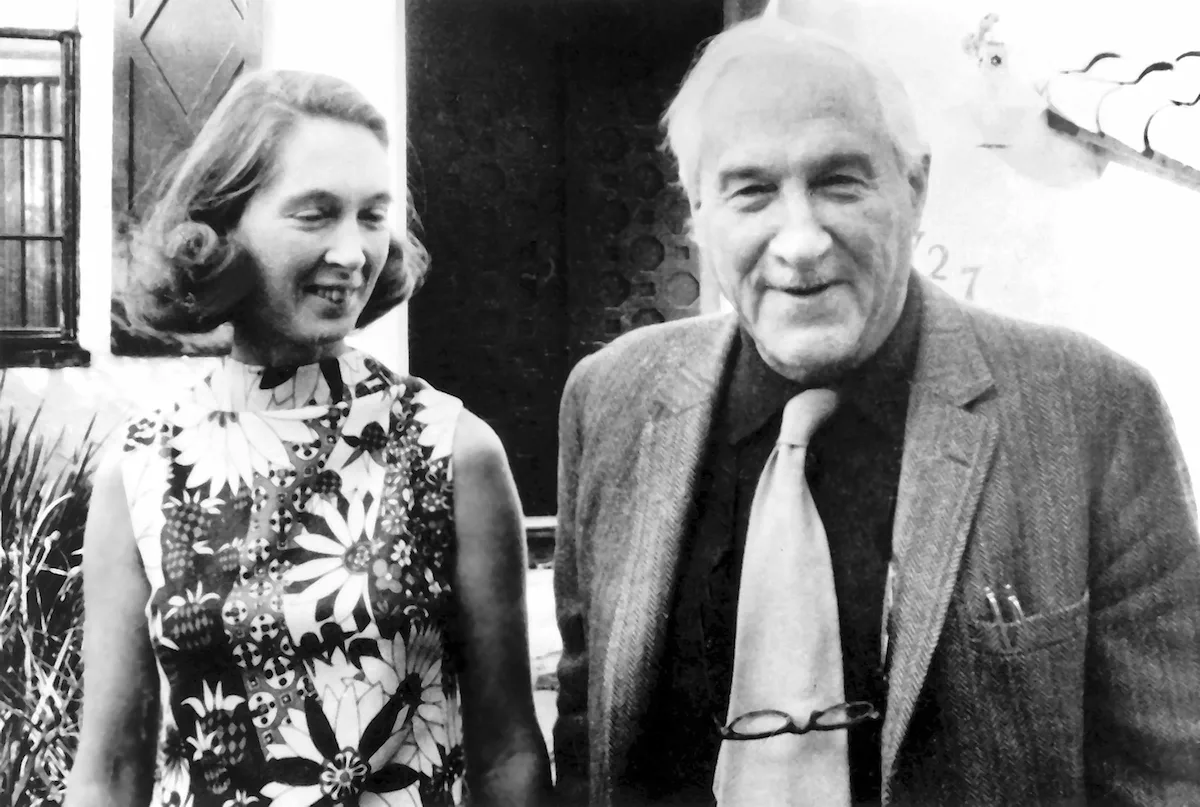

While her research was unfolding in Gombe, the forest was shaping her personal journey too. In 1962, she met Dutch photographer and filmmaker Hugo van Lawick, who had been sent by National Geographic to photograph her. They married in 1964, and their son—Hugo “Grub” Eric Louis van Lawick—was born in 1967.

Van Lawick travelled often for work, and over time their professional paths diverged. They divorced in 1974 but remained on good terms. The following year, Goodall married Derek Bryceson, director of Tanzania’s national parks. Bryceson died of cancer in 1980.12

In 1965 Goodall established the Gombe Stream Research Center. It became a training ground for students interested in primatology, ecology, and related fields, and notably, it attracted many women. That marked a contrast to when Goodall first began her research, at a time when very few women were active in the field.

She would later be recognised as part of a pioneering trio of women chosen by Leakey to study great apes in the wild. Dubbed “the Trimates,” the group included Dian Fossey, who began studying gorillas in Rwanda in 1966, and Birutė Galdikas, who started her research on orangutans in Borneo in 1971.

Her book, My Friends, the Wild Chimpanzees, was published by National Geographic in 1967. It was a huge success—and the first of 32 she would go on to write.

Beyond her scientific achievements, it was the way she lived—simply and reverently—that revealed the depth of her connection to the natural world. She often walked barefoot in the forest and cared little for material possessions.13 While at Gombe, she experienced the world as infused with a profound spiritual presence. ”When you live in the forest, it’s easy to see that everything’s connected,” she said, describing the sense of unity she felt among animals, trees, insects and the forest around her.14

After receiving the Templeton Prize in 2021, she reflected on her time at Gombe in an interview with templetonprize.org:

“When I was in Gombe, I felt very, very close to a great spiritual power. I felt this spiritual power in every living thing. We call it our soul. Well if we have a soul, then that spark of energy is in chimpanzees, they have souls. And the trees, they have a soul, too. They’ve got a spark of that divine energy.”

Her sense of the sacred in all life was reflected in her daily choices. In a 2017 essay, she recalled the moment she chose to give up meat:

“I stopped eating meat some 50 years ago when I looked at the pork chop on my plate and thought: this represents fear, pain, death. That did it, and I went plant-based instantly.”

While her choice was based on ethical and environmental concerns, she also noticed physical changes. “When I stopped eating meat I immediately felt better, lighter,” she said.

Her reverence for life also shaped a broader vision—one that united conservation with community empowerment. In 1977, she founded the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI), initially to continue her work studying and protecting chimpanzees at Gombe. Recognising that caring for wildlife and habitats depends on supporting human well-being, the organisation places communities at the heart of conservation. Today, the JGI operates in 25 countries around the world.

In 1986, Goodall attended a primatology conference in Africa that became a turning point in her career. She noticed a pattern: wherever chimpanzees were being studied, deforestation was also taking place. She left the conference with a new mission—to inspire the next generation to become better caretakers of the natural world and to share that message globally. She also realised she would need to leave Gombe to carry out this work. Reflecting on the experience, she later said, “I went to the conference as a scientist. I left as an activist.”15

Goodall believed that the next generation holds the power to build a more compassionate and sustainable future. “Young people, when informed and empowered, when they realize that what they do truly makes a difference, can indeed change the world,” she said.

In 1991, she founded the Roots & Shoots programme to help young people put compassion and sustainability into action. The initiative focuses on youth, animals, and the environment, encouraging communities to identify local challenges and take steps to address them. What began with a small group of Tanzanian students concerned about the planet’s future has grown into a global movement, now active in more than 75 countries worldwide.

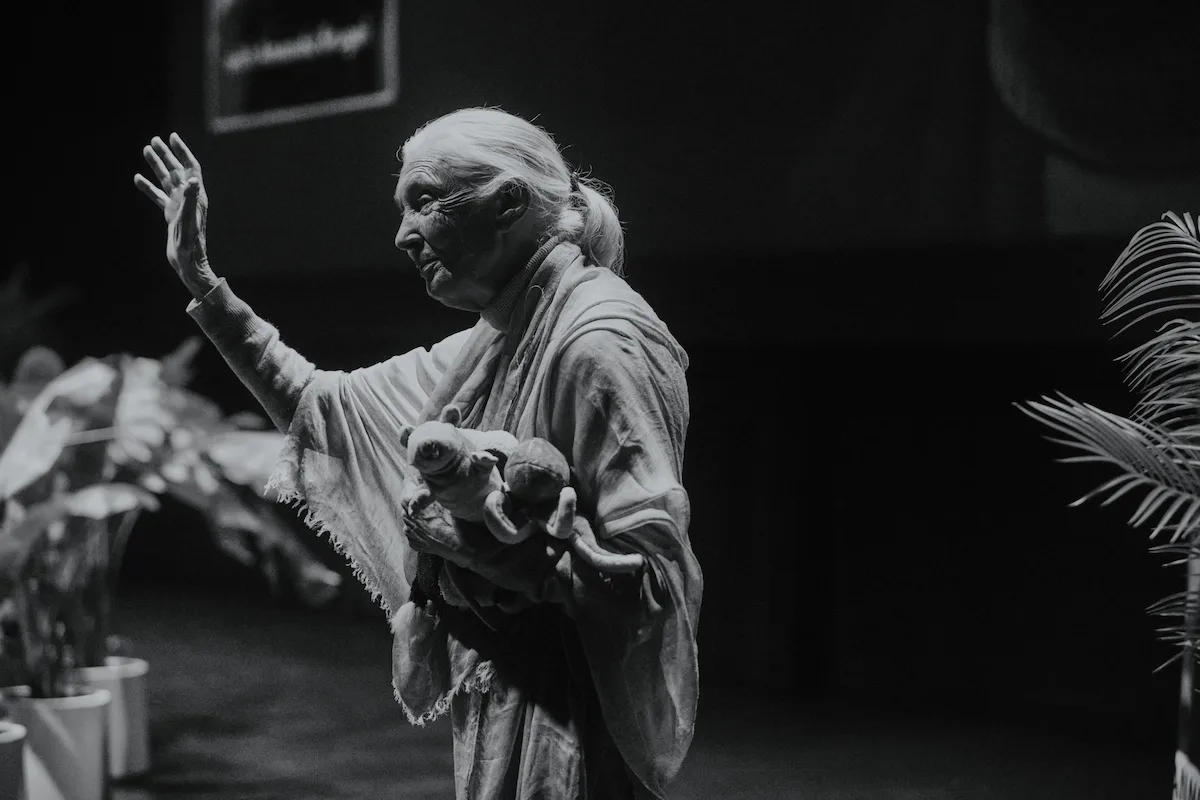

The wild chimpanzee study that Goodall began in Gombe National Park in 1960 continues to this day. Until her passing she continued spreading her message—travelling nearly 300 days a year to give speeches and advocate for wildlife and environmental conservation. She died on 1 October in California while on a U.S. speaking tour. That day, she had been scheduled to speak at a Roots & Shoots school event in Pasadena.

Goodall was known for her grace and compassion, and was widely respected for her ability to engage with people across divides. Yet, in an interview filmed in March 2025 for the Netflix series Famous Last Words, she did not shy away from expressing concern about global leadership and its impact on the planet. The new documentary series features influential public figures who share their reflections and personal convictions, recorded with the understanding that they will only be released after their death.

When asked by host Brad Falchuk if there were people she didn’t like, she responded with unexpected frankness:

“Absolutely, there are people I don’t like, and I would like to put them on one of Musk’s spaceships and send them all off to the planet he’s sure he’s going to discover.”

She went on to list several world leaders whose policies she viewed as harmful to the environment and human rights—a pointed comment that highlighted her deep concern for the future of the planet and leadership’s role in shaping it.

The conversation then turned to the aggressive behaviour of alpha male chimps. Having long recognised the behavioural parallels between humans and chimpanzees, Goodall was something of an authority on alpha male antics.16

After voicing her frustration with the direction of global leadership, Goodall affirmed her belief that most people are fundamentally decent. While acknowledging that the Earth is in “dark times,” one of her final messages in the documentary was a call to keep hope alive:

”We depend on Mother Nature for clean air, for water, for food, for clothing, for everything. And as we destroy one ecosystem after another, as we create worse climate change, worse loss of diversity, we have to do everything in our power to make the world a better place for the children alive today, and for those that will follow. You have it in your power to make a difference. Don’t give up. There is a future for you. Do your best while you’re still on this beautiful Planet Earth that I look down upon from where I am now.”

- Jane Goodall — Inspiring Hope Through Action | WashU ↩︎

- ‘Jubilee’ Plush Toy – #JGI157 | the Jane Goodall Institute Official Store ↩︎

- Dr. Jane Goodall, whose work revolutionized the study of primates, has died | CNN ↩︎

- From Dolittle to Tarzan: What iconic primatologist Jane Goodall read as a child | Books and Literature News – The Indian Express ↩︎

- Jane Goodall ↩︎

- What we learned from Jane Goodall – Geographical ↩︎

- Jane Goodall, conservationist and chimpanzee champion, dies at 91 | National Geographic ↩︎

- How Jane Goodall changed the way we see animals – and the world | New Scientist ↩︎

- Jane Goodall ↩︎

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/jane-goodall-death-primatologist-chimpanzee ↩︎

- Dr. Jane Goodall, whose work revolutionized the study of primates, has died | CNN ↩︎

- https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/us-news/who-were-jane-goodalls-husbands-inside-her-relationships-with-hugo-van-lawick-and-derek-bryceson-101759345893505.html ↩︎

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/jane-goodall-death-primatologist-chimpanzee ↩︎

- The Greatest Danger to Our Future is Apathy for Endangered Species – Jane Goodall’s Good for All News ↩︎

- Dr. Jane Goodall, whose work revolutionized the study of primates, has died | CNN ↩︎

- Jane Goodall’s Posthumous Netflix Special Features A Stellar Burn Of Trump | HuffPost UK Politics ↩︎